Bandersnatch was initially conceived as an interactive episode within the popular Black Mirror anthology series on Netflix. Instead, Netflix decided to release it as a standalone, spin-off film in December 2018. It’s the story of programmer Stefan Butler (Fionn Whitehead) as he adapts a choose-your-own-adventure novel into a video game. Set in 1984, the viewers get to make decisions for Butler’s actions, which then determine the next branch of the story shown to the viewer. They can go back though Bandersnatch and opt for different decisions, in order to experience other versions of the story.

Bandersnatch was written by show creator Charlie Brooker (Black Mirror, Cunk on Britain, Cunk on Shakespeare), directed by David Slade (American Gods, Hannibal, The Twilight Saga: Eclipse), and edited by Tony Kearns (The Lodgers, Cardboard Gangsters, Moon Dogs). I recently had a chance to interview Kearns about the experience of working on such a unique production.

__________________________________________________

[OP] Please tell me a little about your editing background leading up to cutting Bandersnatch.

[OP] Please tell me a little about your editing background leading up to cutting Bandersnatch.

[TK] I started out almost 30 years ago editing music videos in London. I did that full-time for about 15 years working for record companies and directors. At the tail end of that a lot of the directors I was working with moved into doing commercials, so I started editing commercials more and more in Dublin and London. In Dublin I started working on long form, feature film projects and cut about 10 projects that were UK or European co-productions with the Irish Film Board.

In 2017 I got a call from Black Mirror to edit the Metalhead episode, which was directed by David Slade. He was someone I had worked with on music videos and commercials 15 years previously, before he had moved to the United States. That was a nice circularity. We were together working again, but on a completely different type of project – drama, on a really cool series, like Black Mirror. It went very well, so David and I were asked to get involved with Bandersnatch, which we jumped at, because it was such an amazing, different kind of project. It was unlike anything either of us – or anyone else, for that matter – has ever done to that level of complexity.

[OP] Other attempts at interactive storytelling – with the exception of the video game genre – have been a hit-or-miss. What were your initial thoughts when you read the script for the first time?

[TK] I really enjoyed the script. It was written like a conventional script, but with software called Twine, so you could click on it and go down different paths. Initially I was overwhelmed at the complexity of the story and the structure. It wasn’t that I was like a deer in the headlights, but it gave me a sense of scale of the project and [writer/show runner] Charlie Brooker’s ambition to take the interactive story to so many layers.

On my own time I broke down the script and created spreadsheets for each of the eight sections in the script and wrote descriptions of every possible permutation, just to give me a sense of what was involved and to get it in my head what was going on. There are so many different narrative paths – it was helpful to have that in my brain. When we started editing, that would also help me to keep a clear eye at any point.

On my own time I broke down the script and created spreadsheets for each of the eight sections in the script and wrote descriptions of every possible permutation, just to give me a sense of what was involved and to get it in my head what was going on. There are so many different narrative paths – it was helpful to have that in my brain. When we started editing, that would also help me to keep a clear eye at any point.

[OP] How long of a schedule did you have to post Bandersnatch?

[TK] 17 weeks was the official edit time, which isn’t much longer than on a low-budget feature. When I mentioned that to people, they felt that was a really short amount of time; but, we did a couple of weekends, we were really efficient, and we knew what we were doing.

[OP] Were you under any running length constraints, in the same way that a TV show or a feature film editor often wrestles with on a conventional linear program?

[TK] Not at all. This is the difference – linear doesn’t exist. The length depends on the choices that are made. The only direction was for it not to be a sprawling 15-hour epic – that there would be some sort of ball park time. We weren’t constrained, just that each segment had to feel right – tight, but not rushed.

[OP] With that in mind, what sort of process did you do through to get it to feel right?

[TK] Part of each edit review was to make it as tight or as lean as it needed to be. Netflix developed their own software, called Branch Manager, which allowed people to review the cut interactively by selecting the choice points. My amazing assistant editor, John Weeks, is also a coder, so he acquired an extra job, which was to take the exports and do the coding in order to have everything work in Branch Manager. He’s a very robust person, but I think we almost broke him (laughs), because there were up to 100 Branch Manager versions by the end. The coding was hanging on by a thread. He was a bit like Scotty in Star Trek, “The engines can’t hold it anymore, Captain!”

[TK] Part of each edit review was to make it as tight or as lean as it needed to be. Netflix developed their own software, called Branch Manager, which allowed people to review the cut interactively by selecting the choice points. My amazing assistant editor, John Weeks, is also a coder, so he acquired an extra job, which was to take the exports and do the coding in order to have everything work in Branch Manager. He’s a very robust person, but I think we almost broke him (laughs), because there were up to 100 Branch Manager versions by the end. The coding was hanging on by a thread. He was a bit like Scotty in Star Trek, “The engines can’t hold it anymore, Captain!”

By using Branch Manager, people could choose a path and view it and give notes. So I would take the notes, make the changes, and it would be re-exported. Some segments might have five cuts while others would be up to 13 or 14. Some scenes were very straightforward, but others were more difficult to repurpose.

Originally there were more segments in the script, but after the first viewings it was felt that there were too many in there. It was on the borderline of being off-putting for viewers. So we combined a few, but I made sure to keep track of that so it was in the system. There was a lot of reviewing, making notes, updating spreadsheets, and then making sure John had the right version for the next Branch Manager creation. It was quite an involved process.

[OP] How were you able to keep all of this straight? Did you use the common technique of scenes cards on the wall or something different?

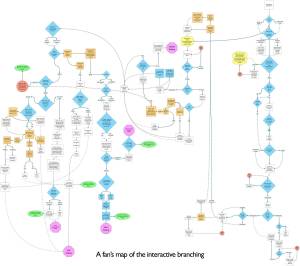

[TK] If you looked at flowcharts your head would explode, because it would be like looking at the wiring diagram of an old-fashioned telephone exchange. There wouldn’t have been enough room on the wall. For us, it would just be on paper – notebooks and spreadsheets. It was more in our heads – our own sense of what was happening – that made it less confusing. If you had the whole thing as a picture, you just wouldn’t know where to look.

[TK] If you looked at flowcharts your head would explode, because it would be like looking at the wiring diagram of an old-fashioned telephone exchange. There wouldn’t have been enough room on the wall. For us, it would just be on paper – notebooks and spreadsheets. It was more in our heads – our own sense of what was happening – that made it less confusing. If you had the whole thing as a picture, you just wouldn’t know where to look.

[OP] In a conventional production an editor always has to be mindful that when something is removed, it may have ramifications to the story later on. In this case, I would imagine that those revisions affected the story in either direction. How were you able to deal with that?

[TK] I have been asked about how did we know that each path would have a sense of a narrative arc. We couldn’t think of it as one, total narrative arc. That’s impossible. You’d have to be a genius to know that it’s all going to work. We felt the performances were great, the story was strong, but it doesn’t have a conventional flow. There are choice points, which act as a propellant into the next part of the film thus creating an unconventional experience to the straight story arc of conventional films or episodes. Although there wasn’t a traditional arc, it still had to feel like a well-told story. And that you would have empathy and a sense of engagement – that it wasn’t a gimmick.

[OP] How did the crew and actors mange to keep the story straight in their minds as scenes were filmed?

[TK] As with any production, the first few days are finding out what you’ve let yourself in for. This was a steep learning curve in that respect. Only three weeks of the seven-week shoot was in the same studio complex where I was working, so I wasn’t present. But there was a sense that they needed to make it easier for the actors and the crew. The script supervisor, Marilyn Kirby, was amazing. She was the oracle for the whole shoot. She kept the whole show on the road, even when it was quite complicated. The actors got into the swing of it quickly, because I had no issues with the rushes. They were fantastic.

[TK] As with any production, the first few days are finding out what you’ve let yourself in for. This was a steep learning curve in that respect. Only three weeks of the seven-week shoot was in the same studio complex where I was working, so I wasn’t present. But there was a sense that they needed to make it easier for the actors and the crew. The script supervisor, Marilyn Kirby, was amazing. She was the oracle for the whole shoot. She kept the whole show on the road, even when it was quite complicated. The actors got into the swing of it quickly, because I had no issues with the rushes. They were fantastic.

[OP] What camera formats were used and what is your preparation process for this footage prior to editing?

[TK] It’s the most variety of camera formats I’ve ever worked on. ARRI Alexa 65 and RED, but also 1980s Ikegami TV cameras, Super 8mm, 35mm, 16mm, and VHS. Plus, all of the print stills were shot on black-and-white film. The data lab handled the huge job to keep this all organized and provide us with the rushes. So, when I got them, they were ready to go. The look was obviously different between the sources, but otherwise it was the same as a regular film. Each morning there was a set of ProRes Proxy rushes ready for us. John synced and organized them and handed them over. And then I started cutting. Considering all the prep the DIT and the data lab had to go through, I think I was in a privileged position!

[OP] What is your method when first starting to edit a scene?

[TK] I watch all of the rushes and can quickly see which take might be the bedrock framing for a scene – which is best for a given line. At that point I don’t just slap things together on a timeline. I try to get a first assembly to be as good as possible, because it just helps anyone who sees it. If you show a director or a show runner a sloppy cut, they’ll get anxious and I don’t want that to happen. I don’t want to give the wrong impression.

[TK] I watch all of the rushes and can quickly see which take might be the bedrock framing for a scene – which is best for a given line. At that point I don’t just slap things together on a timeline. I try to get a first assembly to be as good as possible, because it just helps anyone who sees it. If you show a director or a show runner a sloppy cut, they’ll get anxious and I don’t want that to happen. I don’t want to give the wrong impression.

When I start a scene, I usually put the wide down end-to-end, so I know I have the whole scene. Then I’ll play it and see what I have in the different framings for each line – and then the next line and the next and so on. Finally, I go back and take out angles where I think I may be repeating a shot too much, extend others, and so on. It’s a built-it-up process in an effort to get to a semi-fine cut as quickly as possible.

[OP] Were you able to work with circle takes and director’s notes on Bandersnatch?

[TK] I did get circle takes, but no director’s notes. David and I have an intuitive understanding, which I hope to fulfill each time – that when I watch the footage he shoots, that I’ll get what he’s looking for in the scene. With circles takes, I have to find out very quickly whether the script supervisor is any good or not. Marilyn is brilliant so whenever she’s doing that, I know that take is the one. David is a very efficient director, so there weren’t a massive number of takes – usually two or three takes for each set-up. Everything was shot with two cameras, so I had plenty of coverage. I understand what David is looking for and he trusts me to get close to that.

[OP] With all of the various formats, what sort of shooting ratio did you encounter? Plus, you had mentioned two-camera scenes. What is your approach to that in your edit application?

[TK] I believe the various story paths totaled about four-and-a-half hours of finished material. There was a 3:1 shooting ratio, times two cameras – so maybe 6:1 or even 9:1. I never really got a final total of what was shot, but it wasn’t as big as you’d expect.

[TK] I believe the various story paths totaled about four-and-a-half hours of finished material. There was a 3:1 shooting ratio, times two cameras – so maybe 6:1 or even 9:1. I never really got a final total of what was shot, but it wasn’t as big as you’d expect.

When I have two-camera coverage I deal with it as two individual cameras. I can just type in the same timecode for the other matching angle. I just get more confused with what’s there when I use multi-cam. I prefer to think of it as that’s the clip from the clip. I hope I’m not displaying an anti-technology thing, but I’m used to it this way from doing music videos. I used to use group clips in Avid and found that I could think about each camera angle more clearly by dealing with them separately.

[OP] I understand that you edited Bandersnatch on Adobe Premiere Pro. Is that your preferred editing software?

[TK] I’ve used Premiere Pro on two feature films, which I cut in Dublin, and a number of shorts and TV commercials. If I am working where I can set up my own cutting room, then I’m working with Premiere. I use both Avid and Adobe, but I find I’m faster on Premiere Pro than on Media Composer. The tools are tuned to help me work faster.

The big thing on this job was that you can have multiple sequences open at the same time in Premiere. That was going to be the crunch thing for me. I didn’t know about Branch Manager when I specified Premiere Pro, so I figured that would be the way we work need to review the segments – simply click on a sequence tab and play it as a rudimentary way to review a story path. The company that supplied the gear wasn’t as familiar with Premiere [as they were with Avid], so there were some issues, but it was definitely the right choice.

[OP] Media Composer’s strength is in multi-editor workflows. How did you handle edit collaboration in Premiere Pro?

[TK] We used Adobe’s shared projects feature, which worked, but wasn’t as efficient as working with Avid in that version of Premiere. It also wasn’t ideal that we were working from Avid Nexis as the shared storage platform. In the last couple of months I’ve been in contact with the people at Adobe and I believe they are sorting out some of the issues we were having in order to make it more efficient. I’m keen for that to happen.

[TK] We used Adobe’s shared projects feature, which worked, but wasn’t as efficient as working with Avid in that version of Premiere. It also wasn’t ideal that we were working from Avid Nexis as the shared storage platform. In the last couple of months I’ve been in contact with the people at Adobe and I believe they are sorting out some of the issues we were having in order to make it more efficient. I’m keen for that to happen.

In the UK and London in particular, the big player is Avid and that’s what people know, so anything different, like Premiere Pro, is seen with a degree of suspicion. When someone like me comes in and requests something different, I guess I’m viewed as a bit of a pain in the ass. But, there shouldn’t just be one behemoth. If you had worked on the old Final Cut Pro, then Premiere Pro is a natural fit – only more advanced and supported by a company that didn’t want to make smart phones and tablets.

[OP] Since Adobe Creative Cloud offers a suite of compatible software tools, did you tap into After Effects or other tools for your edit?

[TK] That was another real advantage – the interaction with the graphics user interface and with After Effects. When we mocked up the first choice points, it was so easy to create, import, and adjust. That was a huge advantage. Our VFX editor was able to build temp VFX in After Effects and we could integrate that really easily. He wasn’t just using an edit system’s effects tool, but actual VFX software, which seamlessly integrated with Premiere. Although these weren’t final effects at full 4K resolution, he was able to do some very complex things, so that everyone could go, “Yes, that’s it.”

[TK] That was another real advantage – the interaction with the graphics user interface and with After Effects. When we mocked up the first choice points, it was so easy to create, import, and adjust. That was a huge advantage. Our VFX editor was able to build temp VFX in After Effects and we could integrate that really easily. He wasn’t just using an edit system’s effects tool, but actual VFX software, which seamlessly integrated with Premiere. Although these weren’t final effects at full 4K resolution, he was able to do some very complex things, so that everyone could go, “Yes, that’s it.”

[OP] In closing, what take-away would you offer an editor interested in tackling an interactive story as compared to a conventional linear film?

[TK] I learned to love spreadsheets (laugh). I realized I had to be really, really organized. When I saw the script I knew I had to go through it with a fine-tooth comb and get a sense of it. I also realized you had to unlearn some things you knew about conventional episodic TV. You can’t think of some things in the same way. A practical thing for the team is that you have to have someone who knows coding, if you are using a similar tool to Branch Manager. It’s the only way you will be able to see it properly.

It’s a different kind of storytelling pressure that you have to deal with, mostly because you have to trust your instincts even more that it will work as a coherent story across all the narrative paths. You also have to be prepared to unlearn some of the normal methods you might use. One example is that you have to cut the opening of different segments differently to work with the last shot of the previous choice point, so you can’t just go for one option, you have to think more carefully what the options are. The thing is not to walk in thinking it’s going to be the same as any other production, because it ain’t.

It’s a different kind of storytelling pressure that you have to deal with, mostly because you have to trust your instincts even more that it will work as a coherent story across all the narrative paths. You also have to be prepared to unlearn some of the normal methods you might use. One example is that you have to cut the opening of different segments differently to work with the last shot of the previous choice point, so you can’t just go for one option, you have to think more carefully what the options are. The thing is not to walk in thinking it’s going to be the same as any other production, because it ain’t.

For more on Bandersnatch, check out these links: postPerspective, an Art of the Guillotine interview with Tony Kearns, and a scene analysis at This Guy Edits.

Images courtesy of Netflix and Tony Kearns.

©2019 Oliver Peters