The last century is littered with examples of European powers and the United States attempting to mold foreign governments in their own direction. In some cases, the view at the time may have seemed like these efforts would yield positive results. In others, self-interest or oil was the driving force. We have only to point to the Sykes-Picot Agreement of 1916 (think Lawrence of Arabia) to see the unintended consequences these policies have had in the middle east over the past 100+ years, including current politics.

The last century is littered with examples of European powers and the United States attempting to mold foreign governments in their own direction. In some cases, the view at the time may have seemed like these efforts would yield positive results. In others, self-interest or oil was the driving force. We have only to point to the Sykes-Picot Agreement of 1916 (think Lawrence of Arabia) to see the unintended consequences these policies have had in the middle east over the past 100+ years, including current politics.

In 1953, Britain’s spy agency MI6 and the United States’ CIA orchestrated a military coup in Iran that replaced the democratic prime minister, Mohammad Mossadegh, with the absolute monarchy headed by Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi. Although the CIA has acknowledged its involvement, MI6 never has. Filmmaker Taghi Amirani,  an Iranian-British citizen, set out to tell the true story of the coup, known as Operation Ajax. Five years ago he elicited the help of noted film editor, Walter Murch. What was originally envisioned as a six month edit turned into a four yearlong odyssey of discovery and filmmaking that has become the feature documentary COUP 53.

an Iranian-British citizen, set out to tell the true story of the coup, known as Operation Ajax. Five years ago he elicited the help of noted film editor, Walter Murch. What was originally envisioned as a six month edit turned into a four yearlong odyssey of discovery and filmmaking that has become the feature documentary COUP 53.

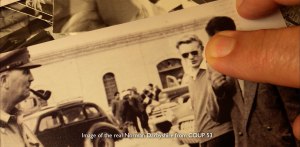

COUP 53 was heavily researched by Amirani and leans on End of Empire, a documentary series produced by Britain’s Granada TV. That production started in 1983 and culminated in its UK broadcast in May of 1985.  While this yielded plenty of interviews with first-hand accounts to pull from, one key omission was an interview with Norman Darbyshire, the MI6 Chief of Station for Iran. Darbyshire was the chief architect of the coup – the proverbial smoking gun. Yet he was inexplicably cut out of the final version of End of Empire, along with others’ references to him.

While this yielded plenty of interviews with first-hand accounts to pull from, one key omission was an interview with Norman Darbyshire, the MI6 Chief of Station for Iran. Darbyshire was the chief architect of the coup – the proverbial smoking gun. Yet he was inexplicably cut out of the final version of End of Empire, along with others’ references to him.

Amirani and Murch pulled back the filmmaking curtain as part of COUP 53. We discover along with Amirani the missing Darbyshire interview transcript, which adds an air of a whodunit to the film. Ultimately what sets COUP 53 apart was the good fortune to get Ralph Fiennes to portray Norman Darbyshire in that pivotal 1983 interview.

COUP 53 premiered last year at the Telluride Film Festival and then played other festivals until coronavirus closed such events down. In spite of rave reviews and packed screenings, the filmmakers thus far have failed to secure distribution. Most likely the usual distributors and streaming channels deem the subject matter to be politically toxic. Whatever the reason, the filmmakers opted to self-distribute, including a virtual cinema event with 100 cinemas on August 19th, the 67th anniversary of the coup.

COUP 53 premiered last year at the Telluride Film Festival and then played other festivals until coronavirus closed such events down. In spite of rave reviews and packed screenings, the filmmakers thus far have failed to secure distribution. Most likely the usual distributors and streaming channels deem the subject matter to be politically toxic. Whatever the reason, the filmmakers opted to self-distribute, including a virtual cinema event with 100 cinemas on August 19th, the 67th anniversary of the coup.

Walter Murch is certainly no stranger to readers.  Despite a long filmography, including working with documentary material, COUP 53 is only his second documentary feature film. (Particle Fever was the first.) This film posed another challenge for Murch, who is known for his willingness to try out different editing platforms. This was the first outing with Adobe Premiere Pro CC, his fifth major editing system. I had a chance to catch up with Walter Murch over the web from his home in London the day before the virtual cinema event. We discussed COUP 53, documentaries, and working with Premiere Pro.

Despite a long filmography, including working with documentary material, COUP 53 is only his second documentary feature film. (Particle Fever was the first.) This film posed another challenge for Murch, who is known for his willingness to try out different editing platforms. This was the first outing with Adobe Premiere Pro CC, his fifth major editing system. I had a chance to catch up with Walter Murch over the web from his home in London the day before the virtual cinema event. We discussed COUP 53, documentaries, and working with Premiere Pro.

___________________________________________________

[Oliver Peters] You and I have emailed back-and-forth on the progress of this film for the past few years. It’s great to see it done. How long have you been working on this film?

[Walter Murch] We had to stop a number of times, because we ran out of money. That’s absolutely typical for this type of privately-financed documentary without a script. If you push together all of the time that I was actually standing at the table editing, it’s probably two years and nine months. Particle Fever – the documentary about the Higgs Boson – took longer than that.

My first day on the job was in June of 2015 and here we are talking about it in August of 2020. In between, I was teaching at the National Film School and at the London Film School. My wife is English and we have this place in London, so I’ve been here the whole time. Plus I have a contract for another book, which is a follow-on to In the Blink of an Eye. So that’s what occupies me when my scissors are in hiding.

My first day on the job was in June of 2015 and here we are talking about it in August of 2020. In between, I was teaching at the National Film School and at the London Film School. My wife is English and we have this place in London, so I’ve been here the whole time. Plus I have a contract for another book, which is a follow-on to In the Blink of an Eye. So that’s what occupies me when my scissors are in hiding.

[OP] Let’s start with Norman Darbyshire, who is key to the storyline. That’s still a bit of an enigma. He’s no longer alive, so we can’t ask him now. Did he originally want to give the 1983 interview and MI6 came in and said ‘no’ – or did he just have second thoughts? Or was it always supposed to be an off the record interview?

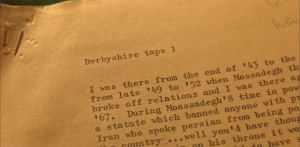

[WM] We don’t know. He had been forced into early retirement by the Thatcher government in 1979, so I think there was a little chip on his shoulder regarding his treatment. The full 14-page transcript has just been released by the National Security Archives in Washington, DC, including the excised material that the producers of the film were thinking about putting into the film.

If they didn’t shoot the material, why did they cut up the transcript as if it were going to be a production script? There was other circumstantial evidence that we weren’t able to include in the film that was pretty indicative that yes, they did shoot film. Reading between the lines, I would say that there was a version of the film where Norman Darbyshire was in it – probably not named as such – because that’s a sensitive topic. Sometime between the summer of 1983 and 1985 he was removed and other people were filmed to fill in the gaps. We know that for a fact.

If they didn’t shoot the material, why did they cut up the transcript as if it were going to be a production script? There was other circumstantial evidence that we weren’t able to include in the film that was pretty indicative that yes, they did shoot film. Reading between the lines, I would say that there was a version of the film where Norman Darbyshire was in it – probably not named as such – because that’s a sensitive topic. Sometime between the summer of 1983 and 1985 he was removed and other people were filmed to fill in the gaps. We know that for a fact.

[OP] As COUP 53 shows, the original interview cameraman clearly thought it was a good interview, but the researcher acts like maybe someone got to management and told them they couldn’t include this.

[WM] That makes sense given what we know about how secret services work. What I still don’t understand is why then was the Darbyshire transcript leaked to The Observer newspaper in 1985. A huge article was published the day before the program went out with all of this detail about Norman Darbyshire – not his name, but his words. And Stephen Meade – his CIA counterpart – who is named. Then when the program ran, there was nothing of him in it. So there was a huge discontinuity between what was published on Sunday and what people saw on Monday. And yet, there was no follow-up. There was nothing in the paper the next week, saying we made a mistake or anything.

[WM] That makes sense given what we know about how secret services work. What I still don’t understand is why then was the Darbyshire transcript leaked to The Observer newspaper in 1985. A huge article was published the day before the program went out with all of this detail about Norman Darbyshire – not his name, but his words. And Stephen Meade – his CIA counterpart – who is named. Then when the program ran, there was nothing of him in it. So there was a huge discontinuity between what was published on Sunday and what people saw on Monday. And yet, there was no follow-up. There was nothing in the paper the next week, saying we made a mistake or anything.

I think eventually we will find out. A lot of the people are still alive. Donald Trelford, the editor of The Observer, who is still alive, wrote something a week ago in a local paper about what he thought happened. Alison [Rooper] – the original research assistant – said in a letter to The Observer that these are Norman Darbyshire’s words, and “I did the interview with him and this transcript is that interview.”

I think eventually we will find out. A lot of the people are still alive. Donald Trelford, the editor of The Observer, who is still alive, wrote something a week ago in a local paper about what he thought happened. Alison [Rooper] – the original research assistant – said in a letter to The Observer that these are Norman Darbyshire’s words, and “I did the interview with him and this transcript is that interview.”

[OP] Please tell me a bit about working with the discovered footage from End of Empire.

[WM] End of Empire was a huge, fourteen-episode project that was produced over a three or four year period. It’s dealing with the social identity of Britain as an empire and how it’s over. The producer, Brian Lapping, gave all of the outtakes to the British Film Institute. It was a breakthrough to discover that they have all of this stuff. We petitioned the Institute and sure enough they had it. We were rubbing our hands together thinking that maybe Darbyshire’s interview was in there. But, of all of the interviews, that’s the one that’s not there.

[WM] End of Empire was a huge, fourteen-episode project that was produced over a three or four year period. It’s dealing with the social identity of Britain as an empire and how it’s over. The producer, Brian Lapping, gave all of the outtakes to the British Film Institute. It was a breakthrough to discover that they have all of this stuff. We petitioned the Institute and sure enough they had it. We were rubbing our hands together thinking that maybe Darbyshire’s interview was in there. But, of all of the interviews, that’s the one that’s not there.

Part of our deal with the BFI was that we would digitize this 16mm material for them. They had reconstituted everything. If there was a section that was used in the film, they replaced it with a reprint from the original film, so that you had the ability to not see any blank spots. Although there was a quality shift when you are looking at something used in the film, because it’s generations away from the original 16mm reversal film.

For instance, Stephen Meade’s interview is not in the 1985 film. Once Darbyshire was taken out, Meade was also taken out. Because it’s 16mm we can still see the grease pencil marks and splices for the sections that they wanted to use. When Meade talks about Darbyshire, he calls him Norman and when Darbyshire talks about Meade he calls him Stephen. So they’re a kind of double act, which is how they are in our film. Except that Darbyshire is Ralph Fiennes and Stephen Meade – who has also passed on – appears through his actual 1983 interview.

For instance, Stephen Meade’s interview is not in the 1985 film. Once Darbyshire was taken out, Meade was also taken out. Because it’s 16mm we can still see the grease pencil marks and splices for the sections that they wanted to use. When Meade talks about Darbyshire, he calls him Norman and when Darbyshire talks about Meade he calls him Stephen. So they’re a kind of double act, which is how they are in our film. Except that Darbyshire is Ralph Fiennes and Stephen Meade – who has also passed on – appears through his actual 1983 interview.

[OP] Between the old and new material, there was a ton of footage. Please explain your workflow for shaping this into a story.

[WM] Taghi is an inveterate shooter of everything. He started filming in 2014 and had accumulated about 40 hours by the time I joined in the following year. All of the scenes where you see him cutting transcripts up and sliding them together – that’s all happening as he was doing it. It’s not recreated at all. The moment he discovered the Darbyshire transcript is the actual instance it happened. By the end, when we added it all up, it was 532 hours of material.

[WM] Taghi is an inveterate shooter of everything. He started filming in 2014 and had accumulated about 40 hours by the time I joined in the following year. All of the scenes where you see him cutting transcripts up and sliding them together – that’s all happening as he was doing it. It’s not recreated at all. The moment he discovered the Darbyshire transcript is the actual instance it happened. By the end, when we added it all up, it was 532 hours of material.

Forgetting all of the creative aspects, how do you keep track of 532 hours of stuff? It’s a challenge. I used my Filemaker Pro database that I’ve been using since the mid-1980s on The Unbearable Lightness of Being. Every film, I rewrite the software slightly to customize it for the film I’m on. I took frame-grabs of all the material so I had stacks and stacks of stills for every set-up.

By 2017 we’d assembled enough material to start on a structure. Using my cards, we spent about two weeks sitting and thinking ‘we could begin here and go there, and this is really good.’ Each time we’d do that, I’d write a little card. We had a stack of cards and started putting them up on the wall and moving them around. We finally had two blackboards of these colored cards with a start, middle, and end. Darbyshire wasn’t there yet. There was a big card with an X on it – the mysterious X. ‘We’re going to find something on this film that nobody has found before.’ That X was just there off to the side looking at us with an accusing glare. And sure enough that X became Norman Darbyshire.

By 2017 we’d assembled enough material to start on a structure. Using my cards, we spent about two weeks sitting and thinking ‘we could begin here and go there, and this is really good.’ Each time we’d do that, I’d write a little card. We had a stack of cards and started putting them up on the wall and moving them around. We finally had two blackboards of these colored cards with a start, middle, and end. Darbyshire wasn’t there yet. There was a big card with an X on it – the mysterious X. ‘We’re going to find something on this film that nobody has found before.’ That X was just there off to the side looking at us with an accusing glare. And sure enough that X became Norman Darbyshire.

At the end of 2017 I just buckled my seat belt and started assembling it all. I had a single timeline of all of the talking heads of our experts. It would swing from one person to another, which would set up a dialogue among themselves – each answering the other one’s question or commenting on a previous answer. Then a new question would be asked and we’d do the same thing. That was 4 1/2 hours long. Then I did all of the same thing for all of the archival material, arranging it chronologically. Where was the most interesting footage and the highest quality version of that? That was almost 4 hours long. Then I did the same thing with all of the Iranian interviews, and when I got it, all of the End of Empire material.

We had four, 4-hour timelines, each of them self-consistent. Putting on my Persian hat, I thought, ‘I’m weaving a rug!’ It was like weaving threads. I’d follow the talking heads for a while and then dive into some archive. From that into an Iranian interview and then some End of Empire material. Then back into some talking heads and a bit of Taghi doing some research. It took me about five months to do that work and it produced an 8 1/2 hour timeline.

We had four, 4-hour timelines, each of them self-consistent. Putting on my Persian hat, I thought, ‘I’m weaving a rug!’ It was like weaving threads. I’d follow the talking heads for a while and then dive into some archive. From that into an Iranian interview and then some End of Empire material. Then back into some talking heads and a bit of Taghi doing some research. It took me about five months to do that work and it produced an 8 1/2 hour timeline.

We looked at that in June of 2018. What were we going to do with that? Is it a multi-part series? It could be, but Netflix didn’t show any interest. We were operating on a shoe string, which meant that the time was running out and we wanted to get it out there. So we decided to go for a feature-length film. It was right about that time that Ralph Fiennes  agreed to be in the film. Once he agreed, that acted like a condenser. If you have Ralph Fiennes, things tend to gravitate around that performance. We filmed his scenes in October of 2018. I had roughed it out using the words of another actor who came in and read for us, along with stills of Ralph Fiennes as M. What an irony! Here’s a guy playing a real MI6 agent who overthrew a whole country, who plays M, the head of MI6, who dispatches James Bond to kill malefactors!

agreed to be in the film. Once he agreed, that acted like a condenser. If you have Ralph Fiennes, things tend to gravitate around that performance. We filmed his scenes in October of 2018. I had roughed it out using the words of another actor who came in and read for us, along with stills of Ralph Fiennes as M. What an irony! Here’s a guy playing a real MI6 agent who overthrew a whole country, who plays M, the head of MI6, who dispatches James Bond to kill malefactors!

Ralph was recorded in an hour and a half in four takes at the Savoy Hotel – the location of the original 1983 interviews. At the time, he was acting in Shakespeare’s Anthony and Cleopatra every evening. So he came in the late morning and had breakfast. By 1:30-ish we were set-up. We prayed for the right weather outside – not too sunny and not rainy. It was perfect. He came and had a little dialogue with the original cameraman about what Darbyshire was like. Then he sat down and entered the zone – a fascinating thing to see. There was a little grooming touch-up to knock off the shine and off we went.

Once we shot Ralph, we were a couple of months away from recording the music and then final color timing and the mix. We were done with a finished, showable version in March of 2019. It was shown to investors in San Francisco and at the TED conference in Vancouver. We got the usual kind of preview feedback and dove back in and squeezed another 20 minutes or so out of the film, which got it to its present length of just under two hours.

[OP] You have a lot of actual stills and some footage from 1953, but as with most historical documentaries, you also have re-enactments. Another unique touch was the paint effect used to treat these re-enactments to differentiate them stylistically from the interviews and archival footage.

[WM] As you know, 1953 is 50+ years before the invention of the smart phone. When coups like this happen today you get thousands of points-of-view. Everyone is photographing everything. That wasn’t the case in 1953. On the final day of the coup, there’s no cinematic material – only some stills. But we have the testimony of Mossadegh’s bodyguard on one side and the son of the general who replaced Mossadegh on the other, plus other people as well. That’s interesting up to a point, but it’s in a foreign language with subtitles, so we decided to go the animation path.

[WM] As you know, 1953 is 50+ years before the invention of the smart phone. When coups like this happen today you get thousands of points-of-view. Everyone is photographing everything. That wasn’t the case in 1953. On the final day of the coup, there’s no cinematic material – only some stills. But we have the testimony of Mossadegh’s bodyguard on one side and the son of the general who replaced Mossadegh on the other, plus other people as well. That’s interesting up to a point, but it’s in a foreign language with subtitles, so we decided to go the animation path.

This particular technique was something Taghi’s brother suggested and we thought it was a great idea. It gets us out of the uncanny valley, in the sense that you know you’re not looking at reality and yet it’s visceral. The idea is that we are looking at what is going on in the head of the person telling us these stories. So it’s intentionally impressionistic. We were lucky to find Martyn Pick, the animator who does this kind of stuff. He’s Mr. Oil Paint Animation in London. He storyboarded it with us and did a couple of days of filming with soldiers doing the fight. Then he used that as the base for his rotoscoping.

This particular technique was something Taghi’s brother suggested and we thought it was a great idea. It gets us out of the uncanny valley, in the sense that you know you’re not looking at reality and yet it’s visceral. The idea is that we are looking at what is going on in the head of the person telling us these stories. So it’s intentionally impressionistic. We were lucky to find Martyn Pick, the animator who does this kind of stuff. He’s Mr. Oil Paint Animation in London. He storyboarded it with us and did a couple of days of filming with soldiers doing the fight. Then he used that as the base for his rotoscoping.

[OP] Quite a few of the first-hand Iranian interviews are in Persian with subtitles. How did you tackle those?

[WM] I speak French and Italian, but not Persian. I knew I could do it, but it was a question of the time frame. So our workflow was that Taghi and I would screen the Iranian language dailies. He would point out the important points and I would take notes. Then Taghi would do a first pass on his workstation to get rid of the chaff. That’s what he would give to the translators. We would hire graduate students. Fateme Ahmadi, one of the associate producers on the film, is Iranian and she would also do translation. Anyone that was available would work on the additional workstation and add subtitling. That would then come to me and I would use that as raw material.

To cut my teeth on this, I tried using the interview with Hamid Admadi, the Iranian historical expert that was recorded in Berlin. Without translating it, I tried to cut it solely on body language and tonality. I just dove in and imagined, if he is saying ‘that’ then I’m thinking ‘this.’ I was kind of like the way they say people with aphasia are. They don’t understand the words, but they understand the mood. To amuse myself, I put subtitles on it, pretending that I knew what he was saying. I showed it to Taghi and he laughed, but said that in terms of the continuity of the Persian, it made perfect sense. The continuity of the dialogue and moods didn’t have any jumps for a Persian speaker. That was a way to tune myself into the rhythms of the Persian language. That’s almost half of what editing is – picking up the rhythm of how people say things – which is almost as important or even sometimes more important than the words they are using.

To cut my teeth on this, I tried using the interview with Hamid Admadi, the Iranian historical expert that was recorded in Berlin. Without translating it, I tried to cut it solely on body language and tonality. I just dove in and imagined, if he is saying ‘that’ then I’m thinking ‘this.’ I was kind of like the way they say people with aphasia are. They don’t understand the words, but they understand the mood. To amuse myself, I put subtitles on it, pretending that I knew what he was saying. I showed it to Taghi and he laughed, but said that in terms of the continuity of the Persian, it made perfect sense. The continuity of the dialogue and moods didn’t have any jumps for a Persian speaker. That was a way to tune myself into the rhythms of the Persian language. That’s almost half of what editing is – picking up the rhythm of how people say things – which is almost as important or even sometimes more important than the words they are using.

[OP] I noticed in the credits that you had three associate editors on the project. Please tell me a bit about their involvement.

[WM] Dan [Farrell] worked on the film through the first three months and then a bit on the second section. He got a job offer to edit a whole film himself, which he absolutely should do. Zoe [Davis] came in to fill in for him and then after a while also had to leave. Evie [Evelyn Franks] came along and she was with us for the rest of the time. They all did a fantastic job, but Evie was on it the longest and was involved in all of the finishing of the film. She’s is still involved, handling all of the media material that we are sending out.

[OP] You are also known for your work as a sound designer and re-recording mixer, but I noticed someone else handled that for this film. What was you sound role on COUP 53?

[WM] I was busy in the cutting room, so I didn’t handle the final mix. But I was the music editor for the film, as well as the picture editor. Composer Robert Miller recorded the music in New York and sent a rough mixdown of his tracks. I would lay that onto my Premiere Pro sequence, rubber-banding the levels to the dialogue.

When he finally sent over the instrument stems – about 22 of them – I copied and pasted the levels from the mixdown onto each of those stems and then tweaked the individual levels to get the best out of every instrument. I made certain decisions about whether or not to use an instrument in the mix. So in a sense, I did mix the music on the film, because when it was delivered to Boom Post in London, where we completed the mix, all of the shaping that a music mixer does was already taken care of. It was a one-person mix and so Martin [Jensen] at Boom only had to get a good level for the music against the dialogue, place it in a 5.1 environment with the right equalization, and shape that up and down slightly. But he didn’t have to get into any of the stems.

When he finally sent over the instrument stems – about 22 of them – I copied and pasted the levels from the mixdown onto each of those stems and then tweaked the individual levels to get the best out of every instrument. I made certain decisions about whether or not to use an instrument in the mix. So in a sense, I did mix the music on the film, because when it was delivered to Boom Post in London, where we completed the mix, all of the shaping that a music mixer does was already taken care of. It was a one-person mix and so Martin [Jensen] at Boom only had to get a good level for the music against the dialogue, place it in a 5.1 environment with the right equalization, and shape that up and down slightly. But he didn’t have to get into any of the stems.

[OP] I’d love to hear your thoughts on working with Premiere Pro over these several years. You’ve mentioned a number of workstations and additional personnel, so I would assume you had devised some type of a collaborative workflow. That is something that’s been an evolution for Adobe over this same time frame.

[WM] We had about 60TB of shared storage. Taghi, Evie Franks, and I each had workstations. Plus there was fourth station for people doing translations. The collaborative workflow was clunky at the beginning. The idea of shared spaces was not what it is now and not what I was used to from Avid, but I was willing to go with it.

Adobe introduced the basics of a more fluid shared workspace in early 2018 I think, and that began a six months’ rough ride, because there were a lot of bugs that came along with that deep software shift. One of them was what I came to call ‘shrapnel.’ When I imported a cut from another workstation into my workstation, the software wouldn’t recognize all the related media clips, which were already there. So these duplicate files would be imported again, which I nicknamed ‘shrapnel.’ I created a bin just to stuff these clips in, because you couldn’t delete them without causing other problems.

Adobe introduced the basics of a more fluid shared workspace in early 2018 I think, and that began a six months’ rough ride, because there were a lot of bugs that came along with that deep software shift. One of them was what I came to call ‘shrapnel.’ When I imported a cut from another workstation into my workstation, the software wouldn’t recognize all the related media clips, which were already there. So these duplicate files would be imported again, which I nicknamed ‘shrapnel.’ I created a bin just to stuff these clips in, because you couldn’t delete them without causing other problems.

Those bugs went away in the late summer of 2018. The ‘shrapnel’ disappeared along with other miscellaneous problems – and the back-and-forth between systems became very transparent. Things can always be improved, but from a hands-on point-of-view, I was very happy with how everything worked from August or September of 2018 through to the completion of the film.

We thought we might stay with Premiere Pro for the color timing, which is very good. But DaVinci Resolve was the system for the colorist that we wanted to get. We had to make some adjustments to go to Resolve and back to Premiere Pro. There were a couple of extra hurdles, but it all worked and there were no kludges. Same for the sound. The export for Pro Tools was very transparent.

[OP] A lot of what you’ve written and lectured about is the rhythm of editing – particularly dramatic films. How does that equate to a documentary?

[WM] Once you have the initial assembly – ours was 8 hours, Apocalypse Now was 6 hours, Cold Mountain was 5 1/2 hours – the jobs are not that different. You see that it’s too long by a lot. What can we get rid of? How can we condense it to make it more understandable, more emotional, clarify it, and get a rhythmic pulse to the whole film?

[WM] Once you have the initial assembly – ours was 8 hours, Apocalypse Now was 6 hours, Cold Mountain was 5 1/2 hours – the jobs are not that different. You see that it’s too long by a lot. What can we get rid of? How can we condense it to make it more understandable, more emotional, clarify it, and get a rhythmic pulse to the whole film?

My approach is not to make a distinction at that point. You are dealing with facts and have to pay attention to the journalistic integrity of the film. On a fiction film you have to pay attention to the integrity of the story, so it’s similar. Getting to that point, however, is highly different, because the editor of an unscripted documentary is writing the story. You are an author of the film. What an author does is stare at a blank piece of paper and say, ‘what am I going to begin with?’ That is part of the process. I’m not writing words, necessarily, but I am writing. The adjectives and nouns and verbs that I use are the shots and sounds available to me.

I would occasionally compare the process for cutting an individual scene to churning butter. You take a bunch of milk – the dailies – and you put them into a churn – Premiere Pro – and you start agitating it. Could this go with that? No. Could this go with that? Maybe. Could this go? Yes! You start globbing things together and out of that butter churning process you’ve eventually got a big ball of butter in the churn and a lot of whey – buttermilk. In other words, the outtakes.

I would occasionally compare the process for cutting an individual scene to churning butter. You take a bunch of milk – the dailies – and you put them into a churn – Premiere Pro – and you start agitating it. Could this go with that? No. Could this go with that? Maybe. Could this go? Yes! You start globbing things together and out of that butter churning process you’ve eventually got a big ball of butter in the churn and a lot of whey – buttermilk. In other words, the outtakes.

That’s essentially how I work. This is potentially a scene. Let me see what kind of scene it will turn into. You get a scene and then another and another. That’s when I go to the card system to see what order I can put these scenes in. That’s like writing a script. You’re not writing symbols on paper, you are taking real images and sound and grappling with them as if they are words themselves.

___________________________________________________

Whether you are a student of history, filmmaking, or just love documentaries, COUP 53 is definitely worth the watch. It’s a study in how real secret services work. Along the way, the viewer is also exposed to the filmmaking process of discovery that goes into every well-crafted documentary.

Images from COUP 53 courtesy of Amirani Media and Adobe.

(Click on any image for an enlarged view.)

You can learn more about the film at COUP53.com.

For more, check out these interviews at Art of the Cut, CineMontage, and Forbes.

©2020 Oliver Peters