Age can sometimes be an impediment to inspired filmmaking, but Francis Ford Coppola, who recently turned 70, has tackled his latest endeavor with the enthusiasm and creativity of a young film school graduate. The film Tetro opened June 11th in New York and Los Angeles and will enter wider distribution in the weeks that follow. Coppola set up camp in a two-story house in Buenos Aires and much of the film was produced in Argentina. This house became the film’s headquarters for production and post in the same approach to filmmaking that the famed director adopted on Youth Without Youth (2007) in Romania.

Tetro is Francis Ford Coppola’s first original screenplay since The Conversation (1974) and is very loosely based on the dynamics within his own family. It is not intended to be autobiographical, but explores classic themes of sibling rivalry, as well as the competition between father and son. Coppola’s own father, Carmine (who died in 1991), was a respected musician and composer who also scored a number of his son’s films. One key figure in Tetro is the family patriarch Carlo (Klaus Brandauer), an acclaimed symphony conductor, who moved as a young music student from the family home in Argentina to Berlin and then to New York. Carlo’s younger son Bennie (Alden Ehrenreich) decided to head back to Buenos Aires in search of his older brother, the brooding poet Tetro (Vincent Gallo) – only to discover a different person than he’d expected.

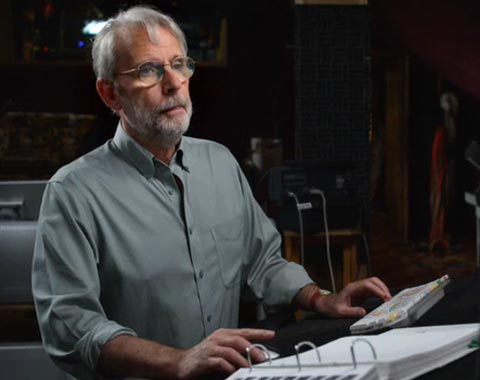

Coppola put together a team of talented Argentine actors and crew, but also brought back key collaborators from his previous films, including Mihai Malaimare, Jr.(director of photography), Osvaldo Golijov (composer) and Walter Murch (editor and re-recording mixer). I caught up with Walter Murch via phone in London, where he spoke at the 1st Annual London Final Cut Pro User Group SuperMeet.

Embracing the American Zoetrope tradition

Tetro has a definite style and vision that sets it apart from current studio fare. According to Walter Murch, “Francis funded Tetro in the same fashion as his previous film Youth Without Youth. He has personal money in it from his Napa Valley winery, as well as that of a few other investors. This lets him make the film the way he wants to, without studio interference. Francis’s directing style is process-oriented – he likes to let the film evolve during the production – to make serendipitous discoveries based on the actors, the sets, the atmosphere of a new city. Many directors work this way, but Francis embraces it more than any other. In Coppola’s own words: ‘The director is the ringmaster of a circus that is inventing itself.’ I think that’s why, at age 69, he was enthusiastic about jumping into a country that was new to him and working with talented young local filmmakers.”

This filmmaking approach is reminiscent of Coppola’s original concept for American Zoetrope Studios . There Coppola pioneered early concepts in electronic filmmaking, hallmarked by the “Silverfish”, an AirStream trailer that provided on-set audio and editing support. Murch continued, “Ideally everything needed to make a Zoetrope film on location should be able to be loaded into two vans. The Buenos Aires building that was our base of operations reminded me of the Zoetrope building in San Francisco 40 years ago. The central idea was to break down the separation between tasks and to be as efficient and collaborative as possible. In other words, to operate more like a film-school crew. Zoetrope also has always embraced new technology – the classic ‘early adopter’ profile. Our crew in Buenos Aires was full of young, enthusiastic local film technicians and artists and on a number of occasions, rounding a corner, I felt like I was bumping into a 40-year-younger version of myself.”

A distinctive visual style

Initial Tetro reviews have commented on the striking visual style of the film. All modern day scenes are in 2.35 wide-screen black-and-white, while flashbacks appear in more classically-formatted 1.77 color. This is Coppola’s second digital film and it followed a similar workflow to that used on Youth Without Youth, shooting with two of the director’s own Sony F900 CineAlta HD cameras. As in the earlier film, the signals from both F900s were recorded onto one Sony SRW field recorder in the HDCAM-SR format. This deck recorded two simultaneous 4:2:2 video streams onto a single tape, which functioned as the “digital negative” for both the A and B cameras.

Simultaneously, another backup recording was made in the slightly more compressed 3:1:1 HDCAM format, using the onboard recorders of the Sony cameras. These HDCAM tapes provided safety backup as well as the working copies to be used for ingest by the editorial team. The HDCAM-SR masters, on the other hand, were set aside until the final assembly at the film’s digital intermediate finish at Deluxe.

Did the fact that this was a largely black-and-white film impact Murch’s editing style? “Not as much as I would have thought,” Murch replied. “The footage was already desaturated before I started cutting, so I was always looking at black-and-white material. However, a few times when I’d match-frame a shot, the color version of the source media would pop up and then that was quite a shock! But the collision between color and black-and-white ultimately provoked the decision to frame the color material with black borders and in a different ‘squarer’ aspect ratio – 1.77 vs. 2.35.”

Changes in the approach

Walter Murch continued to describe the post workflow, “It was similar to our methods in Romania on Youth Without Youth, although with a couple of major differences. Tetro was assembled and screened in 720p ProRes, instead of DV. We had done a ‘bake-off’ of different codecs to see which looked the best for screening without impacting the system’s responsiveness. We compared DVCPRO HD 720 and 1080 with ProRes 720 and 1080, as well as the HQ versions of ProRes. Since I was cutting on Final Cut Pro, we felt naturally drawn to the advantages of ProRes, and as it turned out for our purposes, the 720 version of ProRes seemed to give us the best quality balanced against rendering time. My cutting room also doubled as the screening room and, as we were using the Sim2 digital projector, I had the luxury of being able to cut and look at a 20-foot wide screen as I did so. Another change for me was that my son [Walter Slater Murch] was my first assistant editor. Sean Cullen, my assistant since 2000, was in Paris cutting a film for the first time as the primary editor. Ezequiel Borovinsky and Juan-Pablo Menchon from Buenos Aires rounded out the editorial department as second assistant and apprentice respectively.”

The RED camera has had all the buzz of late, so I asked Murch if Coppola had considered shooting the film with RED, instead of his own Sonys. Murch replied, “Francis is very happy with the look of his cameras, and of course, he owns them, so there’s also a budget consideration. Mihai [Malaimare, DP] brought in a RED for a few days when we needed to shoot with three cameras. The RED material integrated well with the Sony footage, but there is a significantly different workflow, because the RED is a tapeless camera. In the end, I would recommend shooting with one camera or the other if possible. A production shouldn’t mix up workflows unnecessarily.”

Walter Murch discusses future technology

It’s hard to talk film with Walter Murch and not discuss trends, philosophy and technology. He’s been closely associated with a number of digital advances, so I wondered if he saw a competitor coming to challenge either Avid Media Composer or Apple Final Cut Pro for film editing. “It’s hard to see into the future more than about three years,” he answered. “Avid is an excellent system and studios and rental operations have capital investment in equipment, so for the foreseeable future, I think Avid and Final Cut will continue to be the two primary editing tools. Four years from now, who knows? I see more possibility for sooner changes in the area of sound editing and mixing. I’ve done some promising work with Apple’s Soundtrack Pro. The Nuendo-Euphonix combination is also very interesting; but, for Tetro it seemed best to stay compatible with what the sound team was familiar using. Also, [fellow re-recording mixer] Pete Horner and I mixed on the ICON and that’s designed to work with Pro Tools.”

Murch continued, “I’d really like to see some changes in how timelines are handled. I’ve used a Filemaker database for all of my notes now for more than twenty years, starting back when I was still cutting on film. I tweak the database a bit with each film as the needs change. Tetro was the first film where I was able to get the script supervisor – Anahid Nazarian in this case – to also use Filemaker. That was great, because all of the script and camera notes were incorporated into the same Filemaker database from the beginning. Thinking into the future, I’d love to see the Filemaker workshare approach applied to Final Cut Pro. If that were the case, the whole team – picture and sound editors and visual effects – could have access to the same sequence simultaneously. If I was working in one area of the timeline, for example, I could put a ‘virtual dike’ around the section I was editing. The others would not be able to access it for changes, but would see its status prior to my current changes. Once I was done and removed the ‘dike’ the changes would ripple through, the timeline would be updated and everyone could see and work with the new version.”

Stereoscopic 3D is all the rage now, but you may not know that Walter Murch also worked on one of the iconic 3D short films, Captain Eo, starring Michael Jackson. Francis Ford Coppola directed Eo for the Disney theme parks in 1986. It’s too early to tell whether the latest 3D trend will be sustained, but Murch offered his take. “3D certainly has excellent box office numbers right now, but there is still a fundamental perceptual problem with it: Through millions of years of evolution, our brains have been wired so that when we look at an object, the point where our eyes converge and where they focus is one and the same. But with 3D film we have to converge our eyes at the point of the illusion (say five feet in front of us) and simultaneously focus at the plane of the screen (perhaps sixty feet away). We can do this, obviously, but doing it continuously for two hours is one of the reasons why we get headaches watching 3D. If we can somehow solve this problem and if filmmakers use 3D in interesting ways that advance the story – and not just as gimmicks – then I think 3D has a very promising long-term future.”

Written for Videography magazine (NewBay Media, LLC)

© 2009 Oliver Peters