A commercial case study

Upon my return from NAB, I dove straight into post on a set of regional commercials for Hy-Vee, a Midwest grocer. I’ve worked with this client, agency and director for a number of years and all previous projects had been photographed on 35mm, transferred to Digital Betacam and followed a common, standard definition post workflow. The new spots featured celebrity chef Curtis Stone and instead of film, Director/DP Toby Phillips opted to produce the spots using the ARRI ALEXA. This gave us the opportunity to cut and finish in HD. Although we mastered in 1080p/23.98, delivery formats included 720p versions for the web and cinema, along with reformatted spots in 14×9 SD for broadcast.

The beauty of ALEXA is that you can take the Apple ProRes QuickTime camera files straight into edit without any transcoding delays. I was cutting these at TinMen, a local production company, on a fast 12-core Mac Pro connected to a Fibre Channel SAN, so there was no slowdown working with the ProRes 4444 files. Phillips shot with two ALEXAs and a Canon 5D, plus double-system sound. The only conversion involved was to get the 5D files into ProRes, using my standard workflow. The double-system sound was mainly as a back-up, since the audio was also tethered to the ALEXA, which records two tracks of high-quality sound.

On location, the data wrangler used the Pomfort Silverstack ARRI Set application to offload, back-up and organize files from the SxS cards to hard drive. Silverstack lets you review and organize the footage and write a new XML file based on this organization. Since the week-long production covered several different spots, the hope was to organize files according to commercial and scene. In general, this concept worked, but I ran into problems with how Final Cut Pro reconnects media files. Copying the backed-up camera files to the SAN changes the file path. FCP wouldn’t automatically relink the imported XML master clips to the corresponding media. Normally, in this case, once you reconnect the first file, the rest in a similar path will also relink. Unfortunately by using the Silverstack XML, it meant I had to start the reconnect routine every few clips, since this new XML would bridge information across various cards. Instead of using the Silverstack-generated XML, I decided to use the camera-generated XML files, which meant only going through the reconnect dialogue once per card.

It’s worth noting that the QuickTime files written by the ARRI ALEXA somehow differ from what FCP expects to see. When you import these files into FCP, you frequently run into two error prompts: the “media isn’t optimized” message and the “file attributes don’t match” message. Both of these are bogus and the QuickTime files work perfectly well in FCP, so when you encounter such messages, simply click “continue” and proceed.

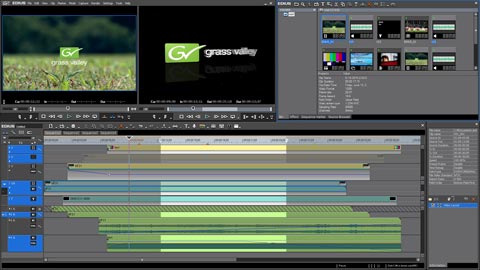

Click for an enlarged view

Dealing with Log-C in the rough cut

As I’ve discussed in numerous posts, one of the mixed blessings of the camera is the Log-C profile. It’s ARRI’s unique way of squeezing a huge dynamic range into the ALEXA’s recorded signal, but it means editors need to understand how to deal with it. Since these spots wouldn’t go through the standard offline-online workflow, it was up to me as the editor to create the “dailies”. I’ve mentioned various approaches to LUTs (color look-up tables), but on this project I used the standard FCP color correction filter to change the image from its flat Log-C appearance to a more pleasing Rec 709 look. On this 12-core Mac Pro, ProRes 4444 clips (with an unrendered color correction filter applied) played smoothly and with full video quality on a ProRes HQ timeline. Since the client was aware of how much better the image would look after grading – and because in the past they had participated in film transfer and color correction sessions – seeing the flat Log-C image didn’t pose a problem.

From my standpoint, it was simply a matter of creating a basic setting and then quickly pasting that filter to clips as I edited them to the timeline. One advantage to using the color correction filter instead of a proper LUT, is that this allowed me to subjectively tweak a shot for the client, without adding another filter. If the shot looked a little dark (compared with a “standard” setting), I would quickly brighten it as I went along. Like most commercial sessions, I would usually have several versions roughed in before the client really started to review anything. In reality, their exposure to the uncorrected images was less frequent than you might think. As such, the “apply filter as you go” method works well in the spot editorial world.

Moving to finishing

New Hat colorist Bob Festa handled the final grading of these spots on a Filmlight Baselight system. There are a couple of ways to send media to a Baselight, but the decision was made to send DPX files, which corresponded to the cut sequence. Since I was sending a string of over ten commercials to be graded, I had a concern about the volume of raw footage to ship. There is a bug in the ALEXA/FCP process and that has to do with FCP’s Media Manager. When you media manage and trim the camera clips, many are not correctly written and result in partial clips with a “-v” suffix. If you media manage, but take the entire length of a clip, then FCP’s Media Manager seems to work correctly. To avoid sending too much footage, I only sent an assembled sequence with the entire series of spots strung out end-to-end. I extended all shots to add built-in handles and removed any of my filters, leaving the uncorrected shots with pad.

Final Cut Pro doesn’t export DPX files, but Premiere Pro does. So… a) I exported an XML from FCP, b) imported that into Premiere Pro, and c) exported the Premiere Pro timeline as DPX media. In addition, I also generated an EDL to serve as a “notch list”, which lined up with all the cuts and divided the long image sequence into a series of shots with edit points – ready to be color corrected.

After a supervised color correction session at New Hat, the graded shots were rendered as a single uncompressed QuickTime movie. I imported that file and realigned the shots with my cuts (removing handles) to now have a set of spots with the final graded clips in place of the Log-C camera footage.

Of course, spot work always involves a few final revisions, and this project was no exception. After a round of agency and client reviews, we edited for a couple of days to revise a few spots and eliminate alternate versions before sending the spots to the audio mixing session. Most of these changes were simple trims that could be done within the amount of handle length I had on the graded footage. However, a few alternate takes were selected and in some cases, I had to extend a shot longer than my handles. This combination meant that about a dozen shots (out of more than ten commercials) had to be newly graded, meaning a second round at New Hat. We skipped the DPX pass and instead sent an EDL and the raw footage as QuickTime ProRes 4444 camera files for only the revised clips. Festa was able to match his previous grades, render new QuickTimes of the revised shots and ship a hard drive back to us.

Click to view “brand introduction” commercial

Reformatting

Our finished masters were ProRes HQ 1920×1080 23.98fps files, but think of these only as intermediates. The actual spots that run in broadcast are 4×3 NTSC. Phillips had framed his shots protecting for 4×3, but in order to preserve some of the wider visual aspect ratio, we decided to finish with a 14×9 framing. This means that the 4×3 frame has a slight letterbox with smaller top and bottom black bars. Unlike the usual 4×3 center-crop, a smaller portion of the left and right edge of the 16×9 HD frame is cropped off. I don’t like how FCP handles the addition of pulldown (to turn 23.98 into 29.97 fps) and I’m not happy with its scaling quality to downconvert HD to SD. My “go to” solution is to use After Effects as the conversion utility for the best results.

From Final Cut, I exported a self-contained, textless QuickTime movie (HD 23.98). This was placed into an After Effects 720 x 486 D1 composition and scaled to match a 14×9 framing within that comp. I rendered an uncompressed QuickTime file out of After Effects (29.97 fps, field-rendered with added 3:2 pulldown). The last step was to bring this 720 x 486 file back into FCP, place it on an NTSC 525i timeline, add and reposition all graphics for proper position and finish the masters.

Most of these steps are not unusual if you do a lot of high-end spot work. In the past, 35mm spots would be rough cut from one-light “dailies”. Transfer facilities would then retransfer selects in supervised color correction sessions and an online shop would conform this new film transfer to the rough cut. Although many of the traditional offline-online approaches are changing, they aren’t going away completely. The tricks learned over the past 40 years of this workflow still have merit in the digital world and can provide for rich post solutions.

Sample images – click to see enlarged view

Log-C profile from camera

Nick Shaw Log-C to Rec 709 LUT (interface)

Nick Shaw Log-C to Rec 709 LUT (result)

Final image after Baselight grading

© 2011 Oliver Peters